In the basement of the house where I grew up there were three things my father kept from his service during the Korean Conflict: a duffle bag, his “Eisenhower Jacket” and a garrison cap. I knew he served in the Army and was in Korea during that war, but not much else about his experience/

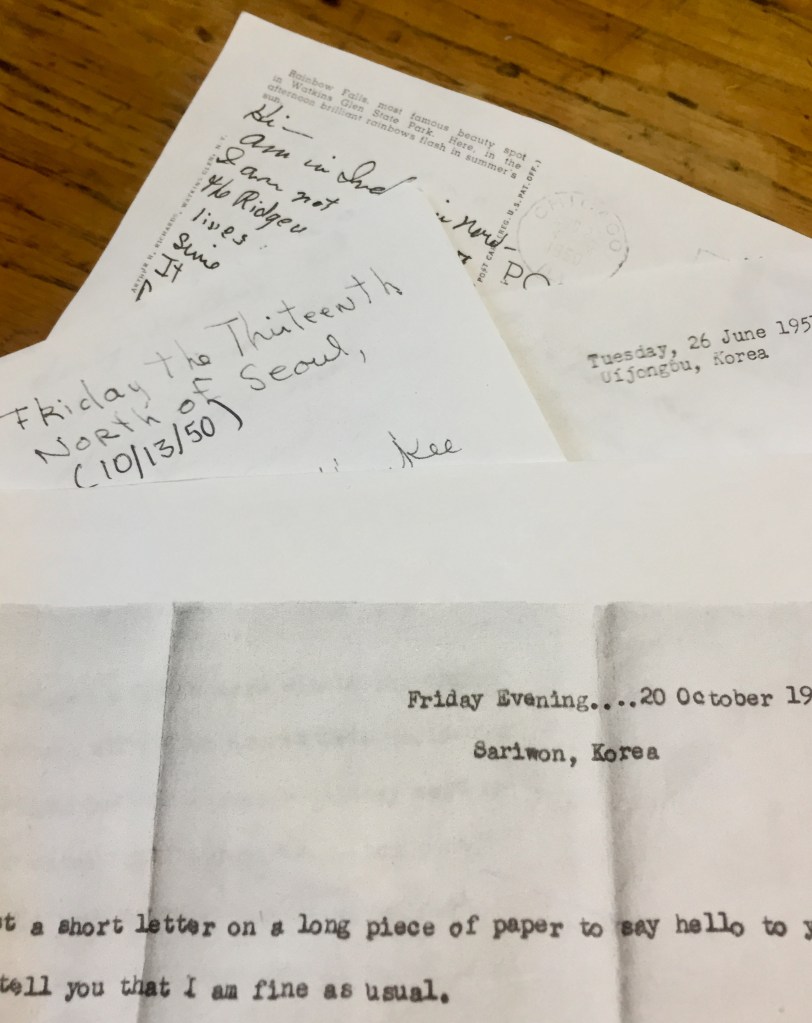

A cousin recently sent me copies of letters my father wrote to his older brother, Earl. They start with a postcard written on August 22, 1950, while on a train headed to Chicago and track my father’s journey from Chicago to Seattle and then to Anchorage, Japan and Korea.

Here is the story they tell.

The conflict my father was traveling towards started two months earlier, on June 25, 1950, when North Korean forces crossed the 38th Parallel intent on unifying the Korean peninsula under Communist rule. The defense of South Korea fell to the Eighth United States Army, which included “I Corps.” My father’s Signal Corps unit supported the headquarters of I Corps.

The North Korean forces came very close to defeating the Eighth Army, but their advance was stopped at what would become known as the Pusan Perimeter.

Initial attempts by the Eighth Army to launch counteroffensives from that perimeter were unsuccessful and resulted in the loss of thousands of lives on both sides. On the day my father left Chicago, the North Korean forces, still numbering nearly 100,000, began what would be their last attempt to breach the Pusan Perimeter.

Three weeks later, on September 15th, the tide of the conflict turned with the amphibious landing of United Nations forces at Inchon. Seoul was liberated and the North Korean forces retreated allowing I Corps and the remainder of the Eighth Army to advance from the Pusan Perimeter and begin a counteroffensive north of the 38th Parallel.

My father made it to Korea and caught up with the 51st Signal Battalion shortly after the Inchon landing.

By October 20th, his unit had reached Sariwon, North Korea, approximately 36 miles from the North Korean capitol. His letter describes a country totally destroyed by invasion, retreat and counter attack:

As you know I am now taking a fast trip through North Korea, courtesy of I Corps. I thought that South Korea was bad enoughly destroyed, but the Air Force, First Cavalry Division, and Republic of Korea troops did not leave a thing when they went through these towns.

He writes of sleeping outside in a small tent in the fresh air. He complains that the northward advance was moving so fast that the food supplies could not keep up and that there has not been a cigarette ration for ten days. He jokes that he may “have to start smoking the North Korean Luckies” if the American cigarettes do not arrive soon.

Five days later, the Chinese entered the conflict and began driving the UN Forces to the South. Seoul would be recaptured by the Chinese and North Korean troops on January 4, 1951, and remain under enemy occupation until liberated a second time by UN forces on March 14th.

My father’s next letter is written two weeks after the second liberation of Seoul and sent from Yeongdeungpo, a district in the southwest of Seoul. Shortly after this letter is sent, Chinese forces would make one last attempt to recapture Seoul and be held off by Canadian, British and Australian forces who are able to delay the Chinese advance long enough for reinforcements to arrive.

The last letter my father sent is dated June 26, 1951. He is in Uijeonbu on the northern outskirts of Seoul. It is hot and he swims twice a day in the Cheonggyecheon tributary to cool off. His uniform is getting “less and less complete and more like a beachcomber’s than a soldier’s.” He works in a tee shirt and fatigue pants and spends as much time possible in bare feet. In closing he mentions that “[t]he big wonder in the past few days has been the possibility of a cease fire and negotiated peace for Korea.”

The hoped for truce talks would start fourteen days later, but would take two years to result in an armistice.

My father’s letters trace the journey of a young soldier from Ithaca who enlisted in the United States Army in 1948, ended up in the Korean Conflict where he saw first hand the devastation and destruction of war. He never shared with anyone other than his brother the story behind the Eisenhower Jacket, duffle bag and cap that he kept in the basement of the house where I grew up.

Until now.